From Focus Magazine – Fall 2018

This is a two-part article about Shorty Harris, Harris Drugs and how they affected Woody Guthrie’s life in Pampa. The first article will cover how he came to be in Pampa and the second will delve into his relationship with Woody and the old Harris Drug Store.

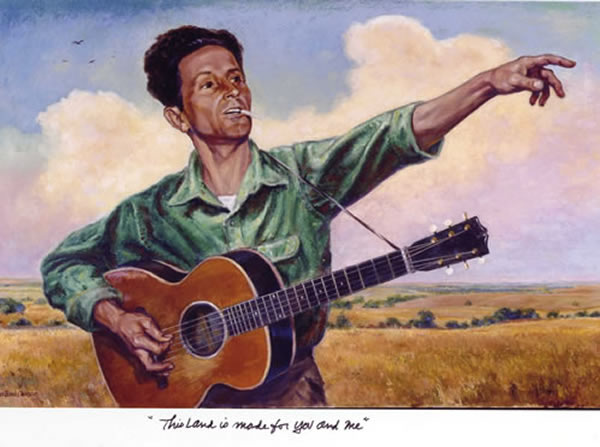

No Shorty Harris, No Bob Dylan?

I read once somewhere that had there been no Woody Guthrie, there would have been no Bob Dylan. By that reasoning, perhaps there would have been no Woody Guthrie if not for Shorty Harris. After all, Shorty did give Woody his first guitar. It was an old beat up thing with rusted strings. Some customer had left it there, probably traded for a drink. While Woody’s uncle, Jeff, was his biggest musical influence at the time, Shorty certainly had a great impact on Woody’s time in Pampa.

While I was going through some old papers at the old Harris Drug Store recently, I came across an interview with Shorty by a Texas A&M faculty member and Pampa native named Sylvia Grider. This interview took place in Pampa on June 8, 1968 in Shorty’s home of 40 years on S. Cuyler Street.

Carl T. “Shorty” Harris was born August 14, 1896 in Conyers (Lathonia), Rockdale County, Georgia, about 20 miles east of Atlanta. In 1899, the family moved to a farm in Rusk County, Texas between the towns of Henderson and Troup. By the time Shorty left home, the family had grown to six boys and nine girls. It is doubtful that he had much formal education because the 1910 Census listed him as 13 years of age with the occupation of ‘farm laborer’. He served in WW1 as a Private First Class, enlisting at Camp Travis in Henderson County. This was in July of 1918. After the war, he came back home and attended Tyler Business School briefly. That experience would serve him well in the years to come.

Being out of money with no prospects, Shorty took work with a large traveling carnival consisting of 31 (railroad) cars in the show; three or four of them were sleepers. He worked in the dining car, learning how to make pies and piecrusts. Later he was to be promoted to short order cook in charge of pastries. This adventure took him to Denver, Wyoming, Montana, Washington, Vancouver and British Columbia. In Centralia, Washington, he got fired for getting into a fight. With $100 in travelers checks (which he lost on the way) and a little loose change (his freight train money) he set out for Los Angeles. Jobs were scarce there and he moved on to Glendale. After a couple of weeks, he headed off to Arizona where he caught a freight train back to Texas. He wound up in San Antonio by mistake and had to find a ride there to take him to Dallas. This was in 1921.

After selling cars in Oklahoma for a while, in 1926, Shorty made friends with an oil field driller and traveled with him to Borger in search of work. Shorty reported, “ Borger was busting open… all kinds of honky- tonks… it was a cyclone…went to a cheap rooming house, got a cot for 50 cents…pad and blanket…after the first night had breakfast and stepped out into the street into a virtual gang fight, the cause of which was unclear and irrelevant. Lots of hustle and bustle… came across another gang fight, eventually retreated back to the hotel. Next morning got some hotcakes for a quarter… then the driller who had found a company to work for decided the conditions were too rough for him and headed off to Pampa on his way back to Oklahoma.” Shorty stayed on in Pampa. His first attempt at a business was a lemonade stand on Brown Street. This venture did not yield much money (even after a hobo showed him how to use citrus powder and lemon slices to save money) so he switched to a small hamburger stand. After hiring a jackleg carpenter to build him a little 8’x10’ fly front store/restaurant, he borrowed 10 pounds of hamburger meat from Thomas Grocery for his first day of operation. More and more people were coming into the area and Shorty built up a pretty good business, next he rented a little shotgun shack of a restaurant from a lady whose business was failing and he built that up for about a year. He bought that building and sold it for a profit. Shorty bought a new car on credit and used his profits to buy a drugstore in the spring of 1928. The Harris Drug Store at 320 S. Cuyler.

In the next article, we will find out about Woody’s relationship with Shorty and a little more about Harris Drugs in the 1930’s.

From Focus Magazine – Winter 2018

Shorty Harris and Woody Guthrie

In the last article I told you how Shorty Harris came about being in Pampa and opening the Harris Drugs at 320 S Cuyler in 1928. Now we will see how Woody came to Pampa, following his father, Charley Guthrie. Charley was a fist-fighting, finagling local politician, hell-bent on success. He taught himself bookkeeping and law, among other things, through avid reading and correspondence courses. Charley had his real, but ultimately short-lived success in land speculation. Politician and real-estate man, he made enough to begin supporting a family and to build them a home. However, in what was to be the first of several tragic fires in Woody’s history, the house burned down in about a month after its completion. In 1920, an oil-boom turned the town of Okemah upside down; gamblers, roughnecks, loose women, and the Ku Klux Klan moved in as well as more cut-throat land speculators who, along with the oil, transformed the business and put an end to Charley Guthrie’s winning streak, making him, as he put it, “the only man who ever lost a farm a day for thirty days.”

The course of Nora Guthrie’s life (Woody’s mother), was equally dramatic. She loved to play the piano and sing the songs that had been passed down to her from her family. It was from Nora that Woody learned many of the old songs and the style, which he would appropriate and adapt for the rest of his life. Nora had Huntington’s chorea, the same disease which Woody came to manifest in his later life, just as his mother had. The disease results in the loss of control over one’s mind and body, and is fatal. Nora’s moods, behavior, and temper were increasingly beyond her control and an increasingly powerful and disturbing force in her family who remained ignorant of the cause. Her behavior was food for town gossip, especially after the death of her eldest daughter, Clara. One day Nora insisted that Clara stay home from school to help with housework, much to Clara’s protest. Ever since the fire, which destroyed their house, Nora had a fear of fires. Clara decided to scare her mother by setting her clothes on fire, intending to put it right out. But she was unable to do so and before her mother could register what was happening, she was up in flames and rolling on the ground in the front yard. A neighbor put the fire out, but not before it had done enough damage to result in Clara’s death the next day.

In 1927, after financial failures and trying relocations, Nora set Charley on fire. Charley survived and Nora was put into an insane asylum where she spent the rest of her life. The truth of these two stories, as Joe Klein tells them, were kept from the family. Clara’s death was thought to be an accident and it was believed that Charley either set himself on fire or suffered an accident as well. A haunting pall of mystery surrounded these incidents for Woody, as it did his entire childhood.

In addition to the family dramas of his childhood, characteristics of his own personality and appearance made Woody a bit of an outsider. It was not long after his father was hospitalized for the burns and his mother put into the asylum that the family relocated to Pampa, Texas. Charley sent his younger children to his sister in Pampa, joining them later. Woody, at the age of 16, lived alone and then with a friend’s family in Okemah for a while, traveled around, visiting relatives and living a bit of a hobo’s life in the summer of 1929, and then joined his family in Pampa.

When Woody arrived in Pampa his father had acquired work from ‘Old Man Eldridge’ who owned the whole block. Most of it was a cot house establishment with about 150 cots. Charley had called it a rooming house, but that was being very generous. It was a long rambling two-story building of cheap pine and corrugated tin. It was part of a sleazy block of hotels, speakeasies and small cafes known as ‘Little Juarez’. The first floor consisted of long rows of cots behind Charlie’s office where he lived. The cots were rented in 8-hour shifts for a quarter. It was called ‘hot cotting’ because one man would get up and another would lay down so the cots never even cooled off. There were young women who lived and worked in the little rooms upstairs. It was Charley’s job to collect the quarters from the oil field hands and the weekly rent from the girls. He was not involved in their other financial business. He was supposed to keep the place relatively clean, or at least, not too disgusting. It was certainly a step down from his former life but his family was glad to have him back up and working after recovering from his terrible burns.

After a year of being mostly on his own, Woody was still only seventeen years old. He seemed younger than that and the girls upstairs treated him like a boy. He drew their pictures and made them laugh. He would also draw pictures of the oil field hands downstairs and his cartoons would appear in the front window, a new one each day. It livened up the dingy street in Little Juarez and delighted Charley that his son showed some promise in this area so he ordered him a correspondence course in cartooning. Charley was big on correspondence courses.

These cartoons attracted the attention of Shorty Harris across the street who decided he would like to brighten up his place too. Shorty’s drugstore was a drugstore in about the same sense that Charley’s place was a rooming house. There were several shelves of faded patent medicines and an ice cream soda fountain. The real business was liquor. It was Prohibition and while it was not legal to sell alcohol there was a provision that you could get a pint every ten days with a prescription from your doctor. This gave little drugstores a legal way to stock liquor.

Woody’s job was to tend to the fountain, fixing banana splits and milk shakes on top of the bar and selling two-ounce bottles of bootleg Jamaica Ginger under the table. Five cents for a root beer and fifty cents for the Jake. Woody decorated the place with cartoons and clever signs in the window and behind the bar on the mirror. He painted Harris Drug on the brick façade above the door. It lasted through the years and the panhandle weather until it was sandblasted off in 1977. It never went totally away though. The paint was part of the brick by now. Thelma Bray and friends had the old outline filled in and it is once again above the door of the old Harris Drugs, now known as The Woody Folk Music Center and The Pampa Visitors Center. Shorty said that Woody also painted signs on the grocery store window every Saturday and he would do quick sketches of people if they wanted.

Woody would get 50 cents to sometimes as much as a dollar a day from Shorty. Wages were cheap in those days and Woody sometimes slept there or the cot house as well. It was not a full time gig as there was not always work for him but it was a good deal for Woody. He was paid daily according to the hours he worked, how entertaining he was or how flush Shorty was that day. If he showed up that was OK and if he didn’t, that was OK too. It seems Shorty just liked having Woody around and Woody must have liked it fine himself.

Shorty Harris was not a short man, his nickname may have come from his short temper. He was known to get rough with customers who got too rowdy and once bit a man’s ear half off in a brawl. He was always good to Woody though and would often loan him money to eat on when there was no work to do. Shorty said Woody was ‘a pretty good worker’. He would chew him out now and then but he never got mad. He was a ‘happy go lucky guy’. He never knew him to fight or argue. He remembered his clothes were not very nice, he did not fit in that way and Shorty felt somewhat sorry for him. He also admired him for his talents and easygoing ways. He would get mad and fire him from time to time, Woody would come back in a day or two, and Shorty would put him back to work.

Woody found a ’beat up old guitar’ in the back of the store that a customer had left according to Shorty. He asked Uncle Jeff to teach him some chords. Jeff was a well-known fiddler in town (as well as a deputy sheriff) and he and Woody developed an immediate rapport. There was no formal instruction, Jeff would just play and Woody would try to keep up. Woody said, “It made good business for Cigar Shorty to have the best fiddle and the worst guitar picker doing their loudest sawing and plinking in his place, and he was glad to have Jeff play on and on”. Woody would sit there in Shorty’s place and try to figure out how to play the old songs he clearly remembered his mother singing. There was a black man who shined shoes next door and Woody particularly enjoyed when he would come over and play some blues. He called him ‘Spider Fingers’ because “his fingers walked up and down that guitar neck just like a big, hairy tarantula”. Shorty recalled Woody started writing songs, hobo songs he called them. So history was born there at Harris Drugs in the summer of 1929 when Shorty Harris met Woody Guthrie.

I could go on and on but if you want more of the story you can read “Woody Guthrie – A Life” by Joe Klein. This is the book that inspired Thelma Bray to start Pampa’s Tribute to Woody Guthrie, which led to purchasing the old Harris Drug Store at 320 S Cuyler St., which would become The Woody Guthrie Folk Music Center. Come by any time Tuesday through Friday from 10am until 5pm and I will be glad to share more of the story with you. On the other hand, if you like you can bring your instrument and sit where Woody played and join our Friday Night Jam Session for old time music and fellowship.